Christ™: A Case for Deontological Faith

“Our idea of God tells us more about ourselves than about Him.” — Thomas Merton

How can one claim truth and love in their life, while their Christian neighbor claims the same, while their agnostic neighbor claims the same, and yet they all remain so oppositional, so false, so certain, so hateful?

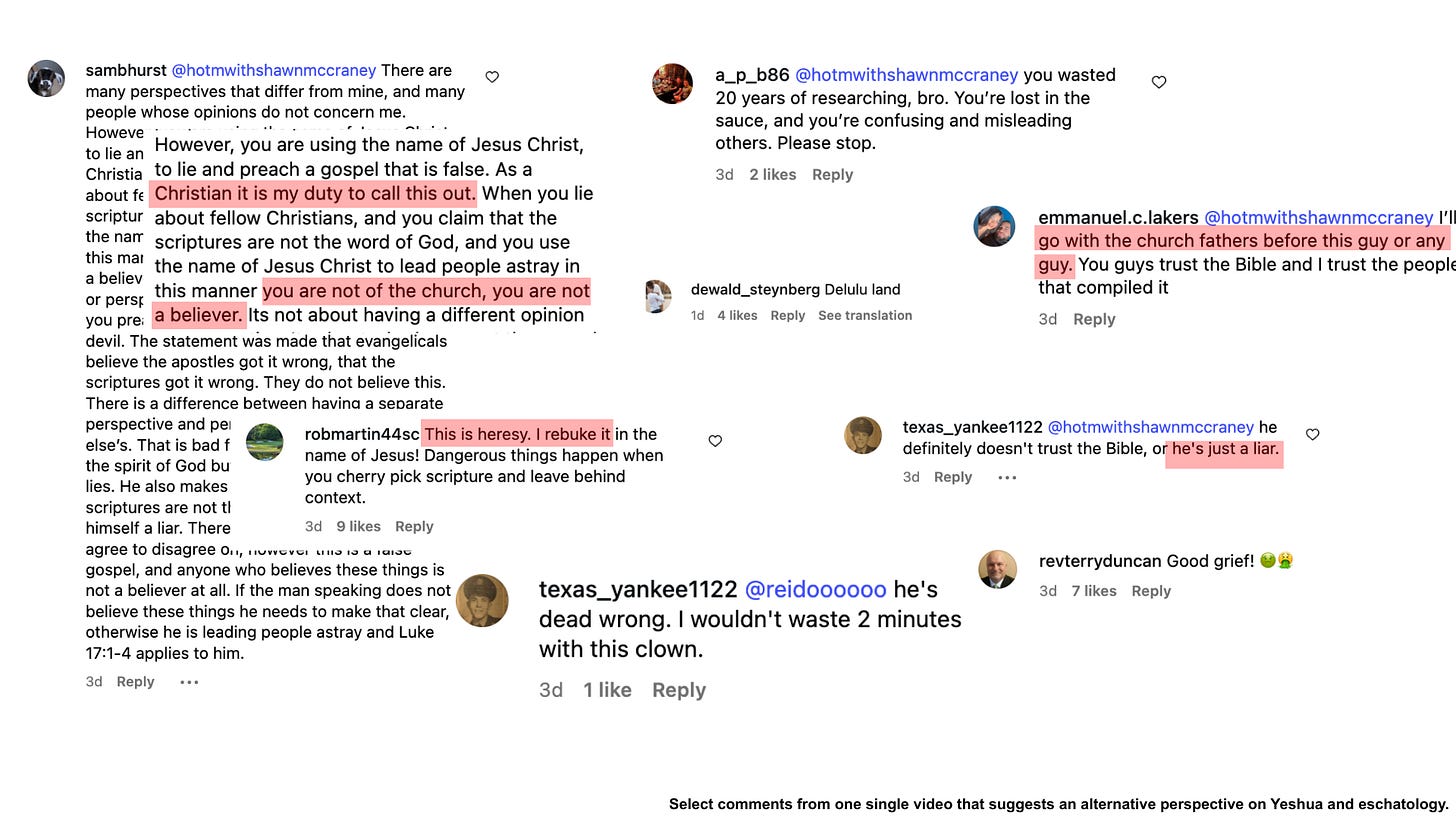

More bewildering still, the closer two individuals are in what they claim to believe, the more hatred seems to exist between them. Three people can claim to follow Christ, and each will despise the other more than they despise their unbelieving friend. It seems consistent that the more similar two views might be, the stronger the hate becomes for their differences.

A non-Christian who encounters a group of Christians is often received with understanding and surface-level kindness. Christians are quick to accept the unbeliever, but that understanding rarely stems from genuine acceptance, it comes from the assumption that this person has simply not yet found the Truth. Patience, in this context, is condescension; their warmth, evangelistic strategy. The love demonstrated is from a place of superiority, backed by the hubris of owned Truth.

But when a believer in Christ differs from the group’s interpretation, the tone changes entirely. Suddenly there is vitriol, condemnation, accusation of evil, and an assignment of the greatest thought-killing title: heretic.

Religion as Collective and Proprietary Truth

This dynamic is not unique to Christianity. It appears wherever a material system of knowledge is linked to an assertion of Truth. The nearer someone’s views are to the system, the more vicious the response when differences appear. Non-essentials are mistaken for essentials, division follows, and destruction results, be it in politics, ideology, or some other religious way of thinking.

Yet in my experience seeking a personal relationship with God through the lens of Yeshua, and not through the lens of religion, none is more vicious than Christianity and its sects. Two thousand years out of touch, Christainity conflates non-essentials with essentials; even the slightest of disagreement is hyperbolically and hatefully cast out as demonic possession or Satanic representation.

When considering the origins / originators of all Christian sects (Yeshua himself, Paul, Peter, Martin Luther, John Calvin, George Fox, Joseph Smith, Arius, Marcion, and others) the comical irony is hard to ignore. These so-called “heretics” were always the ones who later became the foundation of new orthodoxies. Each, in their time, was hated and cast out by the religious consensus; heresy is completely relative, and the term heretic is completely impotent. The prevalence and immediacy of the accusation of “heresy” today, however, proves the pervasive underlying mechanism of modern Christianity: collectivized Truth.

“Good” becomes conflated with consensus, and consensus becomes conflated with Truth, God, salvation, and heaven. “Evil” becomes anything non-conforming, aligned with Lies, Satan, condemnation, and hell. Every orthodoxy is founded upon the heresy that preceded it.

In Christianity, what is deemed essential for “good” is not a deference to God, not the belief that Yeshua was somehow connected to God, not even an epistemological heart-disposition toward truth or faith. It is, rather, an alignment with the consensual authority of a fixed, material understanding of the person, words, and actions of Yeshua as God.

(If you have not experienced any degree of religious hate, it is likely because you have not yet voiced vulnerable thoughts that conflict with orthodoxy. If you want to experience it, try asking questions about the Trinity, about the eternality of Hell, about how Yeshua might relate to God differently than the official formula suggests. Ask if God loves those who reject Christ. Ask about baptism. Ask where the line of atonement is drawn. Just try.)

Religion provides, supports, and enforces the framework for this hatred through the collectivization of Truth. Truth, for religion, is defined through collective mechanisms, consensus, tradition, canon, and logic, each requiring the validation of the group. In religion, Truth becomes proprietary, something owned, distributed, defended by a collective, and individuals are in service of the larger entity.

In secular form, this same impulse appears in various ways like political identity or corporate culture. In Christianity, it manifests as denominations and theological positions. These forms each claim to interpret Truth rightly and exclusively, and the consequence of dissent is disaffiliation: rejection by the collective entity of truth.

The Weaponization of Love through Collectivized Truth

The most difficult aspect of understanding Christianity as a true (and unorthodox) seeker of Yeshua is recognizing that those who claim love as their highest value are often the same people expressing the deepest hate.

For these individuals, hate, whether through division, excommunication, enslavement, and even murder, is accepted as an act of love. They justify it by saying the “most loving thing one can do” is fight for Truth so that others might come to know it. This is plainly stated in nearly all mission statements: defense and correction of Truth. Truth, and God, do not need our defense; the only time you defense becomes intrinsic to Truth is when it is collectively established, because eventually it will crumble in corruption.

This reveals that the collective, proprietary Truth, verified by consensus, tradition, canon, or logic, is what individuals serve. They are not servants of Truth itself, but of the system that claims to possess it. War and murder, of body, mind, or spirit, become the mechanisms of love for religious institutions and individuals.

As long as Truth is collectivized and made proprietary, bringing others into alignment with that Truth becomes the goal, and correction becomes the mechanism for living out morality. Anything done in the name of that goal is said to be loving.

This is teleological thinking: the belief that any means, division, excommunication, discipline, slander, condemnation, murder, war, are justified if the end is someone “finding the Truth.” The purpose sanctifies the cruelty, so long as the cruelty is couched in love.

Humanity’s most bewildering trait is the extent to which hate is inflicted in the name of love; religion functions entirely on this inversion.

Religious love is the correction of an individual to align them with the collective system of Truth. Correction becomes compassion; condemnation becomes care. Love becomes the enforcement of conformity.

In religion, faith is the bridge between an individual’s understanding and the system’s understanding of Truth, not the Truth itself. Masked by language like “you cannot box God in,” religion insists that one must subscribe, by faith, to the box they have already built for Him.

Religionists mistake the system itself for the “thing larger than themselves,” confusing the abstraction with Truth. They appeal to tradition, community, and numbers as evidence that the system must be right. Because the collective believes it owns Truth, any act of correction, exclusion, or even violence is seen as love, justified as necessary to “bring others to God.”

As long as Truth is systematized for collective understanding, it is:

- Made communicable and graspable—therefore reduced and abstracted.

- Necessarily exclusionary—because it cannot allow alternative understandings.

- Branded and proprietary.

- Perpetuated through correction rather than acceptance, all in the name of love.

Collective Teleological Truth vs. Personal Deontological Truth

The collectivized and proprietary Truth that religion defends is motivated through teleological functioning. Teleology measures morality by results; deontology measures it by method.

Religion functions teleologically. It collectivizes a system of Truth, and all moral worth, “good,” “love,” or “faith”, is defined by allegiance to, and evangelism of, that system. The end (someone “finding the Truth”) justifies the means (division, condemnation, control).

But what if Truth itself were deontological?

What if Christ’s entire work was to end teleological functioning – to end religion itself? What if we actually trusted God to bring Truth to individuals, rather than taking up the sword and defending it ourselves? What if we thought God might be more powerful, and doesn’t need us hating each other for Him to get into people’s hearts? What if Christianity finally recognized its unfathomable hubris?

Faith as Individual and Deontological Truth

As described in Material Religion, faith stands as the opposite mechanism to religion. Where religion asserts a material understanding of Truth as the Truth itself, faith maintains a persistent gap between Truth and materiality, dismantling any possibility of collectivizing Truth, and decentralizing the onus of it’s exploration upon the individual.

This shift moves us away from teleological, collective, and hateful religion toward deontological, individual, faith – grounding any resulting love in reality.

When Truth is not collective, it cannot be owned, reduced, or weaponized. It also becomes harder to communicate, lonelier, and slower. Religion paints its most zealous enforcers as soldiers on “the narrow path,” when perhaps the narrow path is narrow because it cannot fit more than one person at a time. It was never meant to be collective.

Deontological pursuit of Truth ventures beyond the systems of consensus and tradition that function efficiently in teleological religion. Deontological faith can only occur individual to individual. Faith is not deference to a system that claims to represent God; it is trust in the living expanse of Truth itself. Love, then, becomes the byproduct of acceptance and long-suffering with others as they do the same.

Teleological religion asserts knowledge through appeals to authority, i.e. consensus, logic, canon, tradition. It punishes defiance, calls faith a trust in the proprietary system of understanding God (not in God directly), and names any means to enforce conformity to this faith love.

Deontological faith acknowledges its lack of knowledge, sets its authority in Truth itself, and pursues that Truth personally. It shows love not out of superiority or the desire to correct, but out of humility, the hope of learning and expanding more.

Faith Can and Will Never Be Collective

So, why is it that two individuals can claim Christ, yet their dispositions appear entirely different?

One prescribes to religion; the other prescribes to Christ himself.

Religion weaponizes Truth and calls it love.

Faith embodies Love and calls it Truth.

When Truth becomes property, love becomes the price of admission.

When Truth is living, love becomes its only proof.

Christ dismantled the collective mechanisms that make Truth ownable: temple, priesthood, law, and nation. Christianity, meaning any attempt to make Christ collectively knowable, rebuilt them all.

Deontological faith refuses to use love as a means to an end. It loves because love is the end, knowing that Truth can never be fully agreed upon. Deontological faith is when an individual appeals to Christ directly, without inflicting that pursuit upon another.

Where religion demands agreement, faith demands humility.

Where religion breeds hate, faith breeds mercy.

Only the individual can know Christ, and only when it remains individual can love finally exist.

Responses